Imperial Circuits: Intertwined Histories of Militarism and Anti-Imperialist Resistance Between Panamá and the U.S. Southeast

“being in the diaspora

is being

murdered

without ever bleeding”

— Palestinian poet Yaffa As

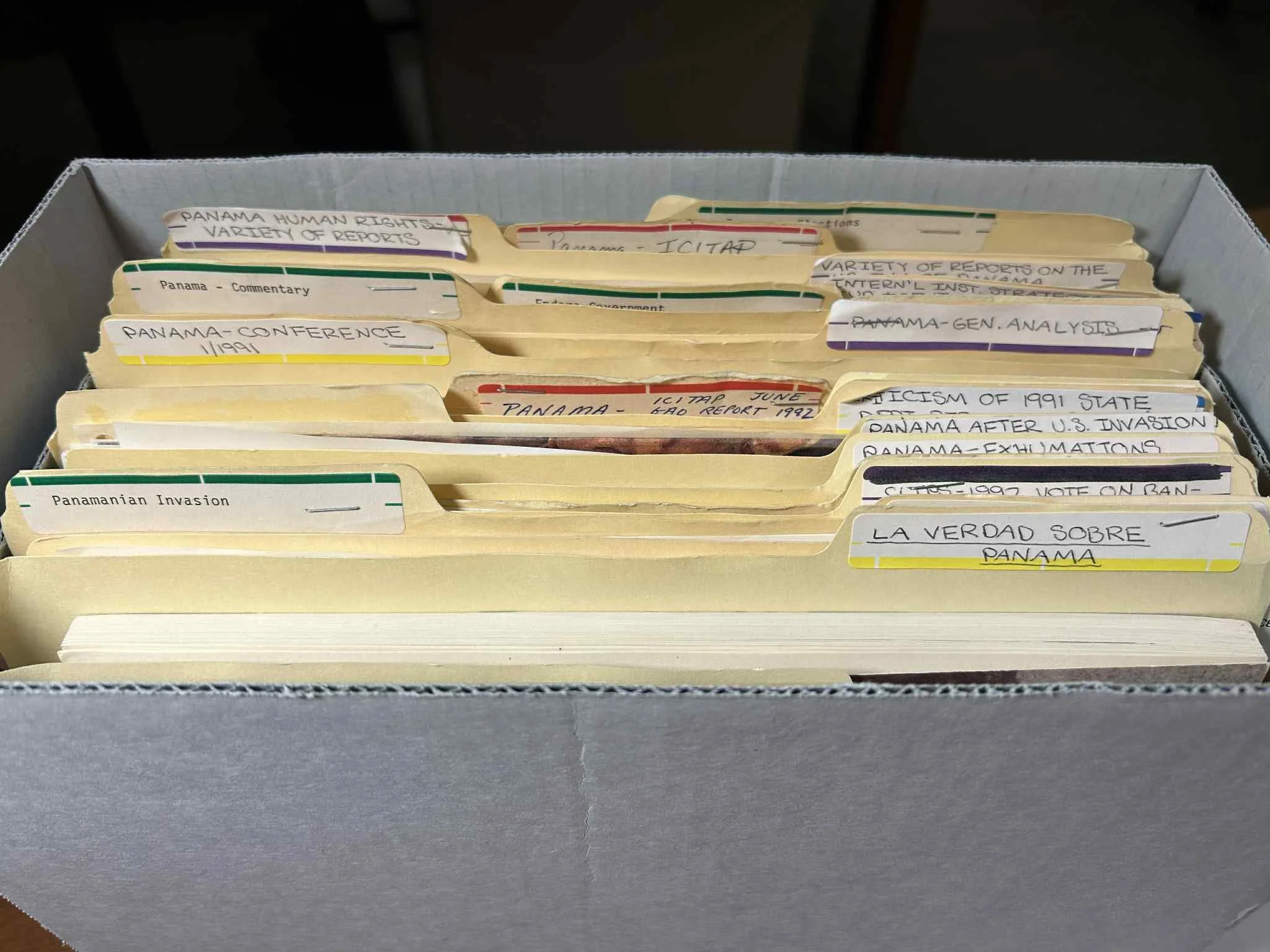

Photograph I took at the Duke University Rubenstein Library while conducting archival research on Panama.

For the past few months, I have been obsessing over archives – their deep resonances across time and geography, as well as their possibilities and limitations. My daily routine has consisted of walking the short route from my apartment to Duke University’s East Campus, taking the shuttle to the Rubenstein Library, and then spending hours hunched over any Panama, School of the Americas (SOA), and Central American solidarity archives I could find. This was my first time ever conducting archival research on my own. I was inspired by our program, Vos del Sur: Central American Studies from the Global/U.S. South, an independent political education course for Central American participants in the U.S. Southeast to explore the intertwined histories of our motherlands with the region many of us, or our families, migrated to.

The materials I encountered at the library ranged from 1980s campus activism pamphlets to yellowed mainstream media clippings to copies of official state records, such as a 1984 Committee on Foreign Affairs hearing memo on the role of the U.S. Southern Command (SOUTHCOM) in Central America. The archives, like the broader program itself, revealed the interconnected histories of militarism, their ensuing legacies of death and destruction, and people’s transnational resistance – from the Global South to the U.S. South. These connections resonated deeply with me as someone who grew up in Central America, migrated to Georgia, and now resides in Durham, North Carolina. My own family’s pattern of movement from Panama to Georgia, for instance, mirrors that of U.S. military installations that have historically inflicted violence all across Latin America, like the SOA and SOUTHCOM, previously based in Panama then relocated to the U.S. South, as I explore in this piece.

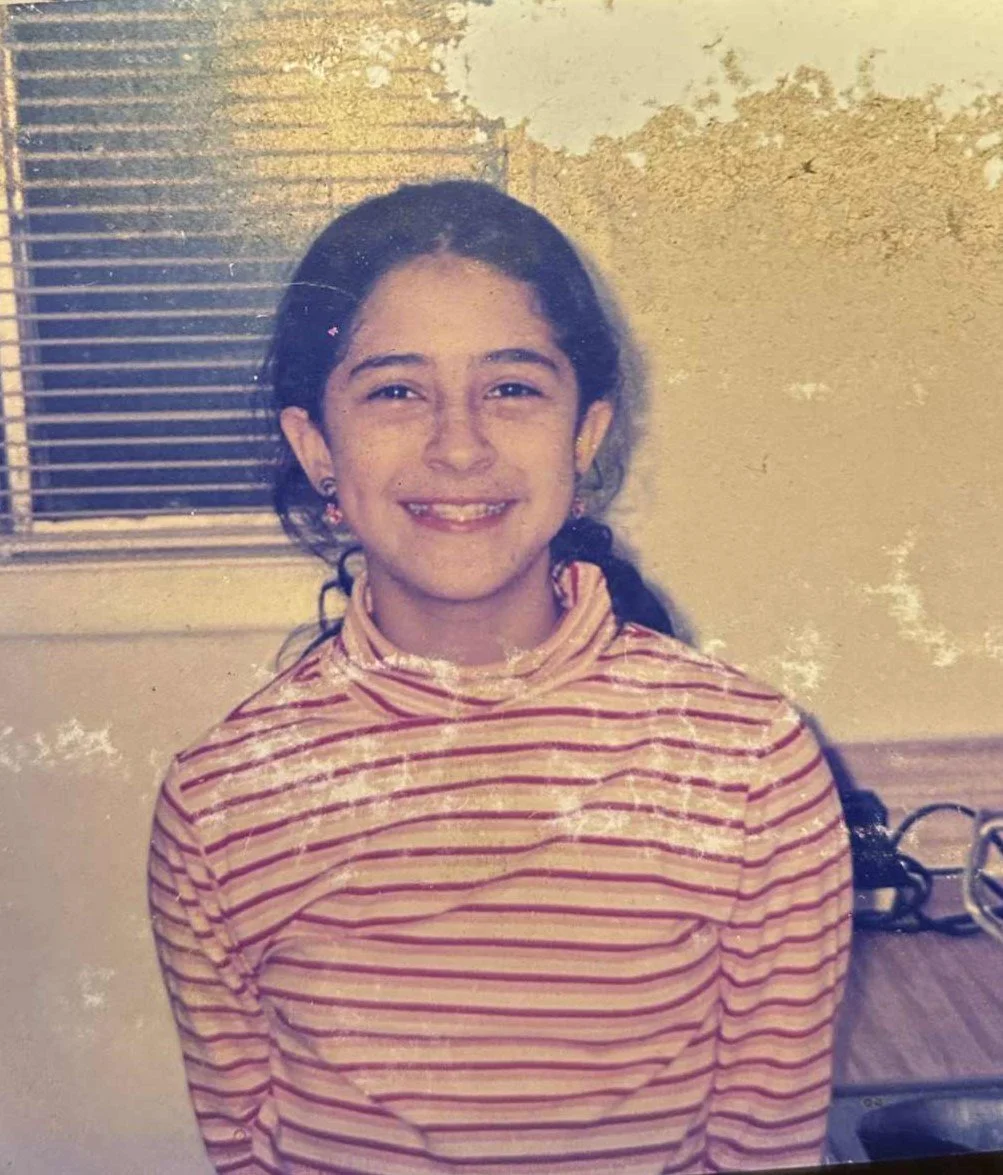

Me when I first migrated to Atlanta, Georgia in 2005.

Thinking about my family’s journey and encountering these sources, made me ask: What makes the U.S. South a historically, economically, and militarily unique space not just in the United States, but also on the global stage? Why is it important to recover and make meaning of these connections as Central American immigrants and the children of immigrants living in the U.S. South today? What can we learn from the legacies of internationalist, working-class, and cross-racial resistance in the South, particularly the Black Radical Tradition? Why do these questions matter in our current political climate?

These questions matter in today’s context because, even earlier this summer in June, news headlines reported that the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency “brokered a deal with private prison company GEO” to double the size of its processing center in Folkston, Georgia, which will make it the largest ICE detention center in the country. Simultaneously with the heightened crackdown on immigrants that has been met with resistance (and repression) all over the United States, the current U.S. friendly-Panamanian government has repressed mass protests decrying the return of U.S. military presence, plans to reactivate a large open-pit copper mine, and threats to privatize social security. Our planetary fight – rooted in the systems of global capitalism and imperialism – is clearly far from over.

Circuits of Racialized Violence and Militarism

As I wrote in a previous publication for Migrant Roots Media, Panama has historically been of interest to the United States government and military because of its strategic economic and military location as a transoceanic isthmus. At its height, the United States had approximately 100 military bases in Panama. Like the SOA – now rebranded as the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC) in Fort Benning, Georgia – SOUTHCOM, a joint command center of the U.S. Department of Defense, was also based in the Panama Canal Zone (PCZ) and then relocated to the U.S. South in Miami. For its more than fifty years of existence, the goal of SOUTHCOM has been to “defend” Central America, South America, the Caribbean and, specifically, the Panama Canal. We must ask: defend it from who, and for whom?

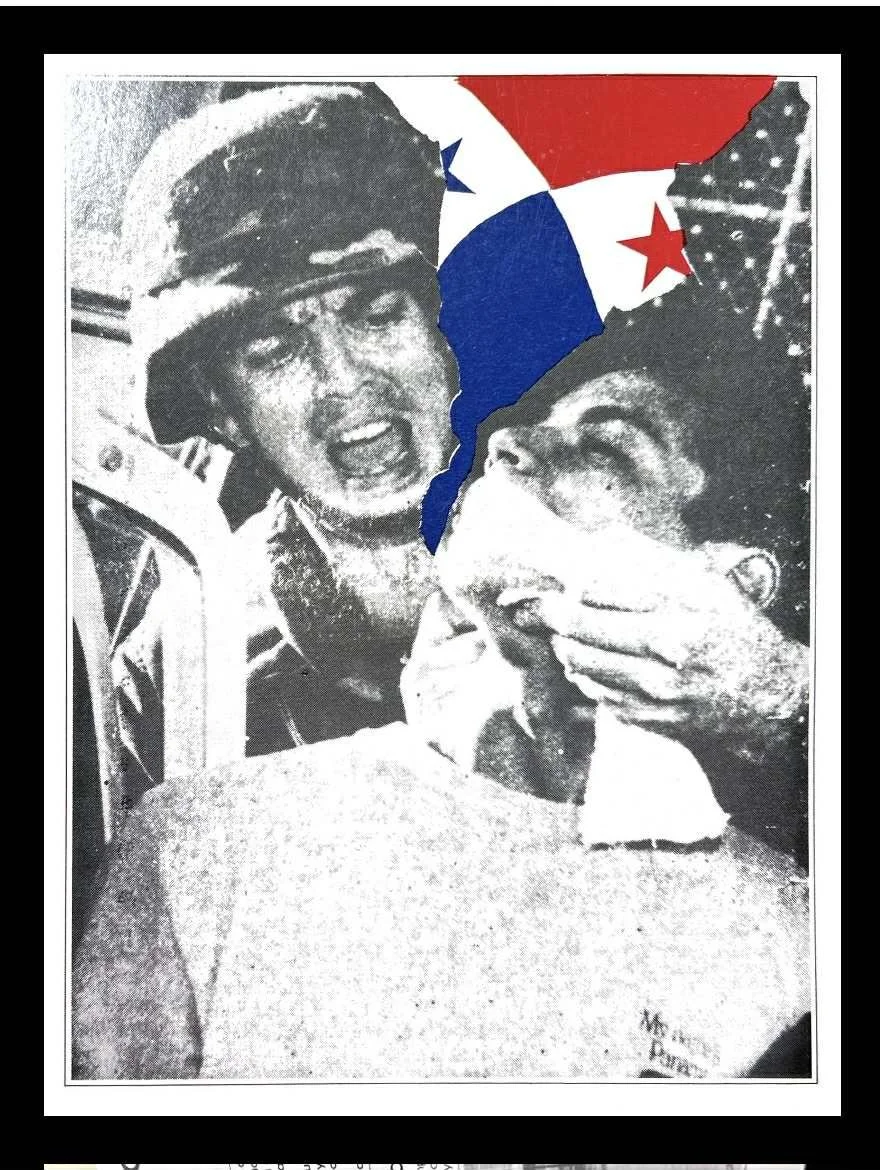

Protest mural against the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama painted on the exterior of the May 5 station of the Panama metro.

A 2009 SOUTHCOM report reveals material U.S. interests in preserving military control over the region, “As the U.S. continues to require more petroleum and gas, Latin America is becoming a global energy leader with its large oil reserves and oil and gas production and supplies.” However, U.S. interest in maintaining dominance over the entire Western hemisphere dates back even further to the 1823 Monroe Doctrine and its 1904 Corollary, which essentially established the United States as Latin America’s “top cop.” In today’s context, as I thought about my own patterns of migration from Panama to Georgia throughout the course of the program, I asked myself: why were these military installations meant to exert control over Latin America transferred from Panama to the U.S. South specifically?

While the answer partially lies in tales of lobbying on behalf of politicians and businesspeople, the U.S. South – in both its material conditions and geography, like Panama – is also a uniquely attractive space for the military. Labor and military historian Arthur Braswell highlights that the U.S. South has a disproportionate concentration of military installations relative to its population. He partly attributes this to the South’s climate (i.e. heat for year-round training), reliable access to water due to its river systems, sandy soils used for discarding lead bullets (particularly in the physiographic region of The Sandhills in South Carolina), as well as low wages and historical attacks on organized labor that created a more exploitable population of soldiers, including many Black U.S. Americans. In particular, the Black Belt region of the United States, encompassing hundreds of counties from Texas to Virginia, mainly in Alabama and Mississippi, “hosts a high concentration of military bases, suggesting the strategic importance of controlling the region, and the significance of war for the area’s economy.” The Black Belt, known for its fertile soil, has been characterized as resembling “the situation of the colonized world” because it was the epicenter of slavery and the cotton plantation economy and remains a majority Black region and hub for U.S. manufacturing. Like the Global South, its land and people have been and continue to be hyper-exploited.

In her important study on the SOA, anthropologist Lesley Gill tells the story of how anti-communist Cuban businesspeople lobbied Congress for the SOA to be relocated to Georgia by arguing that there was something specific about white Southern culture that could successfully instill “real” U.S. American values upon the “foreign” soldiers who might have been sympathetic to the revolutionary processes of late twentieth-century Latin America. In effect, this was a campaign to “Americanize” the soldiers in the country’s most historically repressive region with a deep legacy of white supremacy and slavery, but also the cradle of the nation’s most revolutionary movements, from abolitionists struggling under the most oppressive conditions to Black Reconstruction to the Civil Rights Movement to Black Communist and internationalist organizing in the 1980s and beyond.

At the archives, I felt an overwhelming mix of inspiration at the recorded histories of radical Central American solidarity networks that existed here in Durham long before I arrived in 2018, as well as deep grief at the first-hand testimonies of survivors of the 1989 U.S. invasion of Panama meant to oust CIA puppet and SOA trainee General Manuel Noriega after he turned against U.S. government interests. One testimony from a mother who lived in a housing project in El Chorrillo, the majority Black, working-class neighborhood most impacted by the U.S. attacks, reads:

“Casi no podíamos creerlo, mi niño lloraba aterrorizado, mi hermana y yo solo atinábamos a protegerlo con nuestros cuerpos. A cada bombazo el edificio se estremecía y se quebraban vidrios, entre las detonaciones y explosiones se escuchaban gritos de dolor y miedo.”

The woman dragged two gas tanks from the kitchen to the bathroom, which she considered the safest area of the house, in order to prevent them from exploding if impacted by bullets. She hid in the bathroom alongside her seven-year-old son, sister, and their dog until the “gringos” ordered them to exit the building at eight in the morning. Two days later, on December 22, 1989, the woman returned to the news that her neighbors, an Indigenous Guna woman and her child who was the same age as her own, had been killed. She recalls walking up the hallway to the apartment, “Se sentía un horrible olor a muerto, creo que nunca me voy a olvidar de ese olor, como tampoco voy a olvidar las bombas, los incendios, las balas, los cadáveres y los cuerpos mutilados.” As diasporic Central Americans, painful testimonies like this one – often resulting from U.S.-sponsored violence in collusion with our country’s corrupt elites – are too familiar.

Scan of a graphic I found at the archives depicting military aggression against civilians in Panama.

Many of the Black Panamanians who lived and were assassinated in El Chorrillo had worked in the PCZ, a U.S.-controlled apartheid enclave where the racist Jim Crow policies of the U.S. South had been imported, like scholars Kaysha Corinealdi and Joan Flores-Villalobos have written about. The neighborhood, located close to Panamanian Defense Force barracks at the edge of the Canal Zone, was made up largely of single and two-story wooden homes first built to house Canal workers during its construction, and then PCZ workers. Investigative journalist Michael Fox writes, “[The U.S. government and troops] knew the whole area would go up in smoke like a box of matches. That’s what they were shooting for.” For the United States to violently murder a majority racialized population that they had exploited and subjected to their own imported system of racist subjugation is abhorrent. Yet, these imperial nodes of violence can be traced in different ways all over the world, particularly in the Global South.

Circuits of Multiracial, Transnational Resistance

“As the South goes, so goes the nation.”

— W. E. B. Dubois

I held back tears as I glanced through some of the testimonies recounting the many human rights abuses committed in Panama, and even laughed as I came across some of the official U.S. media communications and state documents justifying the attacks and, more broadly, U.S. military violence in Latin America. However, it was also extremely heart-warming and inspiring to come across archives documenting the presence of a vibrant Central America Solidarity movement in Durham and at Duke University, where I now live and work, and which I hope to further explore in future articles.

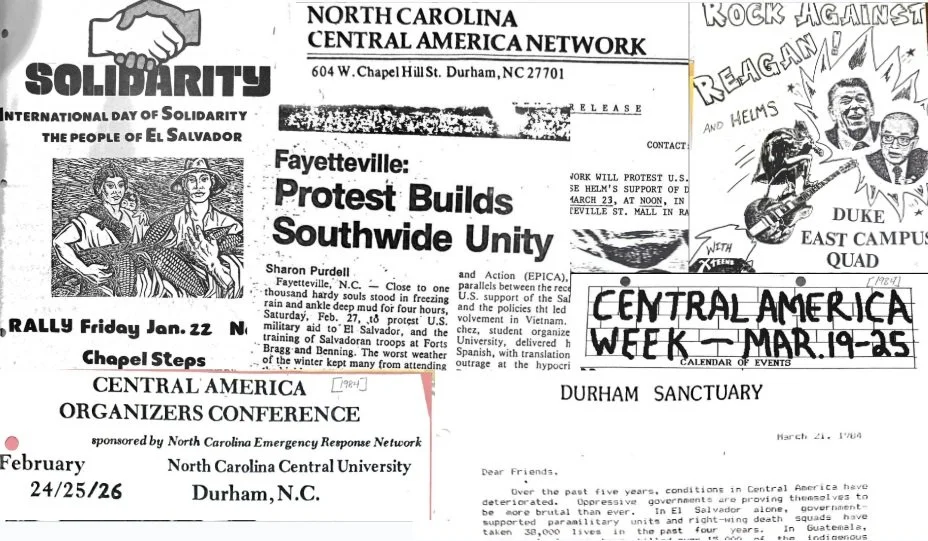

Collage I created from scans of documents I found at the archives exemplifying North Carolina solidarity with Central America in the 1980s.

While it is not totally surprising that the Durham community was engaged in Central American solidarity work since this was a nationwide movement in the 1980s, it was grounding for me to come across specific pamphlets, meeting minutes, press releases, event flyers, and more detailing how broad the demonstrations of solidarity truly were. Some of the active groups in the North Carolina Triangle included Duke University’s Central America Solidarity Committee, Witness for Peace (Durham), the Carolina Interfaith Taskforce on Central America (Chapel Hill), the Durham Action Committee on Central America, and the War Resisters League Southeast. Encountering these movement archives led me to understand my own work today within a large context of interfaith and multiracial organizing for Central America in Durham.

Throughout our Vos del Sur classes and in my research, however, one connection became particularly central: the importance of the Black Radical Tradition when thinking about historical resistance in the U.S. South. Similarly to how Central Americans were painted as Communist agitators to justify the dirty U.S.-sponsored wars of the 1970s and 1980s, Black communists were targeted in the United States, including in the U.S. South as Charisse Burden-Stelly writes in her book, Black Scare, Red Scare. One such instance was the bloody Greensboro Massacre of 1979 in North Carolina, during which Klansmen and Nazis targeted and murdered in broad daylight five communists, including Black communists, who had participated in a “Death to the Klan” march.

About two hours southeast from Greensboro in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, the organization Black Workers for Justice (BWFJ) was founded in 1981 largely by Black women conscious of their combined race, gender, and class-based exploitation. Historian Ajamu Dillahunt-Holloway, currently working on an important book on the history of BWFJ, writes about the organization’s international solidarity with struggles around the world, including with Central America, “Like it did with apartheid in South Africa, BWFJ felt that the Black working class was connected to and had a responsibility to oppose United States imperialism.” Dillahunt-Holloway’s own grandmother, Rukiya Dillahunt, a founding member of BWFJ, participated in a 1986 Black and Third World Delegation to Nicaragua with Witness for Peace. In an interview with The Carolinian that same year, Dillahunt declared, “Standing with the people of Nicaragua is no different than opposing apartheid in South Africa or police brutality in Raleigh or racist violence in Kittrell.” Linking these international networks of oppression is crucial for understanding how empire works to oppress both internationally and domestically, particularly as we are witnessing heightened attacks on immigrant populations from the Trump administration.

These circuits of both oppression and resistance are brilliantly described by Palestinian-American activist, legal scholar, and human rights attorney Noura Erakat in an article about the Demilitarize! Durham2Palestine campaign, which successfully ended the Deadly Exchange program between the Durham Police Department and the Israeli police and military in 2018. Erakat argues that “Black–Palestinian solidarity continues to function as an anti-imperial analytic” that connects how the tactics, technologies, and ideologies used to oppress racialized populations in other parts of the world are the same ones used internally to target mostly working-class Black and Brown communities in the United States. This analytic can be applied to the parallel struggles of all racialized diasporas in the United States, including Central Americans.

Screenshots from Aida’s zine.

As I uncovered these archives and even worked on writing this piece, I wrestled with the contradiction of what it means for many of these documents to be housed in an institution with historical and ongoing investments in the military industrial complex. In a zine she created, Aida, a Duke student and daughter of Chinese immigrants, cites the 1986 arrests of six student protesters opposing Duke’s $26 million investments in corporations doing business with the apartheid South African government. She ends the zine with a call to engage in mutual aid, radical art and zine-making, and political education. Today, groups like Students for Justice in Palestine, Duke Staff and Academics for Justice in Palestine, and the newly re-activated Duke Chapter of Migrant Roots Media continue this critical anti-imperialist work within the institution. Beyond the university, community programs like Vos del Sur follow in this courageous movement legacy and foster spaces of learning beyond the confines of the Ivory Tower. Funny how institutions with investments in militarism and other types of violence often sow the seeds of their own resistance.

Me returning to Panama for the first time in almost twenty years in February 2024.

Alejandra (Ale) Mejía is the Chief Editor of Migrant Roots Media. Her politics and commitment to migrant justice are largely informed by her lived experiences as a working-class Central American immigrant in the U.S. South. She is an Assistant Editor at Duke University Press, where she acquires books in Latine/x history, and an editor for Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research.