Vos del Sur: Elevating Central American Voices from the Global/U.S. South

On July 3, 2024, a great friend, Taina Figueroa, hosted a birthday celebration that brought her various circles together – scholars, organizers, artists, and homies. Felipe Hinojosa, a historian, mentor, and friend, was conducting archival research in his former stomping grounds of Atlanta and planned to celebrate Taina as well. He invited one of his friends, Alejandra Mejía.

“You two have to meet,” Felipe said as he walked me over to introduce me to Ale. In our conversation, Ale and I learned that we were both Central American – she, Honduran and Panamanian, and I, Salvadoran and Guatemalan. Ale noted that we already followed each other on social media. The more we talked, the more parallels and connections we found with each other. She grew up close to Buford Highway, where I now live, and she attended the local schools where I now work and teach. Around 2007, her family moved to Norcross in Gwinnett County, the same county where I grew up. It was not an uncommon story: Latine/xs in Georgia frequently move between Buford Highway and Gwinnett County. We were stunned to see that we both had a tattoo of the Central American isthmus on our arms. The map of our ancestral region was etched onto our bodies as a commitment to our people. Our encounter was meant to be.

Our alignment grew even more as we talked about our research interests and how we have always wanted to take a Central American studies class that explored our experiences as Southerners. In fact, telling the stories of the Latine/x South and radical movements in the South is central to both of our work. Ale acquires books in Latine/x history for an academic press and is Chief Editor for an anti-imperialist, migrant-run media and educational organization, Migrant Roots Media. I am an educator and researcher in Latine/x and Central American studies, focusing on Central America-U.S. South connections.

As the night neared its end, Ale needed to make her way home. I happened to live ten minutes away from her mother’s, where she was staying, so I offered her a ride. We kept chatting, dreaming, and eventually arrived at the question: “What if we started a Central American studies of the U.S. South class together?” We identified our resources, assessing our institutional and personal capacities. Within a month, Ale and I, with support from the Founding Director of Migrant Roots Media, Roxana Bendezú, founded the program Vos del Sur: Central American Studies from the Global/U.S. South.

Building an Ethnic Studies of the U.S. South

My mother arrived in Los Angeles in 1991, a year before the brutal civil war in El Salvador came to an end. She brought with her few belongings, including a work visa and memories of carnage and poverty. These scattered stories of pain and violence shaped my understanding of her distant home country growing up, a country I would not see until I decided to visit as an adult, much to my mother’s dismay. Her sporadic stories were steeped in trauma; the silences and shame that enveloped this distant place raised questions for me about why this country hurt my mother so much. When I was around two or three years old, we moved from my birthplace of Los Angeles to find a life away from a Guatemalan father who created strife in my mother’s life. My mom hoped to find a better life surrounded by our family in Long Island, New York, a hub for many Salvadorans.

Jonathan as a child with his mother and siblings.

After a few years in New York, my mother, stepfather, siblings, and I made our way from the diverse metropolis of New York to the rural factory town of Springdale, Arkansas. Like other Latine/xs before us motivated by labor and the potential for opportunity beyond the urban cityscape, we arrived in Arkansas and became exposed, in our schools and within the labor force, to the particular anti-immigrant racism and segregation of the South. The antagonisms that I saw and experienced between Mexican and Salvadoran students taught me that Salvadorans and Central Americans like me experienced the world differently, though I was unsure of how and why. Later, when Arkansas and its chicken processing plants did not provide my single mother with the support she needed to raise three children and earn a fair wage, we made our way to metro-Atlanta, Georgia. Atlanta, an urban center of the South, showed me the complexity and diversity of this post-plantation landscape and society which continue to criminalize, villainize, and disenfranchise families like mine.

In all that we do, the personal is political. I stepped foot on the campus of Emory University in 2014, excited for the opportunity to be the first in my family to go to college. I came to college with the intent of becoming a teacher focused on equity and empowerment in schools like the ones I had attended in Arkansas and Georgia – underresourced and racially and ethnically diverse yet segregated. In these schools, Latine/x, Black, Asian, immigrant, and low-income students like my peers and I were not served with a high-quality education like the white, wealthier students in nearby schools. This was not because particular teachers did not care about their students or try to improve conditions. It was systemic and institutional neglect, the disenfranchisement of youth of color – a story typical of the U.S. American schooling system.

My educational experiences informed my goals to become a K-12 educator, but college courses in sociology, gender studies, and African American studies along with research fellowships at Emory, drove me to consider a career in academia and shaped my ethnic studies education. Down the Latine/x studies rabbit hole I went, learning from the Chicane/x studies and Puerto Rican studies traditions. I decided I wanted to become a social scientist and scholar of Latine/x studies to write the histories and document the experiences of Latine/xs like me.

Deep in my ethnic studies rabbit hole, I learned that the first department of Central American studies in the United States was founded at California State University, Northridge (CSUN). Looking further, I saw that Central American studies classes were offered at CSUN, East Los Angeles College, and the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA). I emailed my friend and mentor, Dr. Marisela Martinez-Cola, a Chicana doctoral candidate at the time, with excitement and in all-caps. I wrote something along the lines of, “LOOK I’M RELEVANT! MY COMMUNITY IS RELEVANT!” What a gift it was to know that my and my family’s experiences were deserving of critical and compassionate study, especially by people like me, even if it was not in my state of residence.

As I learned more about the field of Central American studies, I also forged myself into a student-researcher of ethnic studies and Latine/x studies. I was on track to becoming a PhD student myself, but I knew that I wanted to connect my research to organizing. I wanted to use research as a tool for social and political change, especially for my Latine/x and Central American community. In 2016, as a sophomore at Emory, I read the Los Angeles Times feature about Gaspar Marcos, a Guatemalan high school student who arrived in Los Angeles as an unaccompanied minor. While I did not arrive in the United States as an unaccompanied minor myself, it was then that I realized that I needed to tell the stories of Central American youth like me in the South, stories which often go untold.

But Georgia was not California. Latine/x studies, Chicane/x studies, and Central American studies had deep roots in the movement legacies of California and the Southwest. The Southeast was still figuring out what to do with us. Our universities, especially an elite, historically white private university like Emory, were not responsive to the needs of Latine/x first-generation students without pressure. Emory did not yet have a department of Latine/x studies or U.S. Latine professors of Latine/x studies, so it became an organizing goal for my peers and I throughout our time at Emory. My first Latine/x studies class was a Latine/x social movements course taught by the visiting Mexican-American professor who would later introduce me to Ale, Felipe Hinojosa, in Spring 2018. From both his class and years of gradual organizing, the “Consciousness is Power” movement was born at Emory to continue the legacy of Black, Latine/x, and Asian American students fighting for the ethnic studies classes and university that we deserved.

At Emory, I committed myself to building spaces and institutions for Latine/x and Central American students in the South to connect to our ancestors, histories, and movement legacies so that we could be empowered to fight for a different world. I was especially committed to building Central American consciousness in the U.S. South, where migrants and U.S.-born Central Americans have been separated from our identities and histories because of assimilation, our parents’ war trauma, and through omission from school curricula, among others. In his 2019 piece, “Central American studies was the most important class I ever took,” Salvadoran journalist Daniel Alvarenga writes:

“[W]hen the kids at the border are freed from their cages, it’s our duty to have more than Hollywood depictions of maids, guerrillas and gangs looking back at them. That when they grow up and deal with their trauma, they’ll have a body of work to look to and validate their experiences. They deserve to know about the resilience of our people, how we fought back against oppression, and how we’ve carved out our survival in this country.”

The kind of education that can heal our connections to ourselves, each other, and our lands must exist in every university through ethnic studies departments with specific programs dedicated to different identities. However, the university should not have a monopoly on or authority over a truly liberating ethnic studies education. I am committed to bringing Ivory Tower knowledge and resources back to its rightful place: the people.

However, I also understand that ethnic studies education in Georgia, while drawing from previous models and predecessors, must look different from the ethnic studies traditions of California and Arizona that I have become a student of. We do not have the infrastructure, elders, mentors, and institutions – at least in recent memory – to organically build a movement for Latine/x studies in Georgia and the South. Because of the Black liberation struggle in the South, some seeds for ethnic studies education in the region have already been sown. Indigenous ways of knowing from the Southeastern peoples have also enriched the soil. Still, these decolonial and community education traditions have largely been forgotten or obscured. Latine/xs, and specifically Central Americans, I believe, can benefit from an educational model that acknowledges the wisdom of the U.S. South and its people while cross-pollinating with Global South traditions that migrant diasporas bring with them, thus creating a Global U.S. South.

Over the years, I have delved into the history of ethnic studies and liberatory pedagogy through self-study, graduate study in education and history, and relationships with mentors in California and Arizona. I came to understand that an ethnic studies of the Global/U.S. South had to first and foremost acknowledge and learn from the Indigenous peoples of the Southeast who were forcibly displaced alongside the legacy of slavery and Black resistance in the plantation South. Core tenets of an ethnic studies of the Global/U.S. South must acknowledge that settler colonialism, slavery, and imperialism are the master projects of white supremacy and capitalism. Moreover, we must learn from the traditions of Global Southerners (“Third World” people). As I use it, the term “Global Southerners” refers to people originating from Africa, Asia, Latin America, and their descendants. Among the Global South groups that guide me are the Third World Liberation Front, the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords, the Chicano Movement, the Cuban and Nicaraguan literacy campaigns, Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire, and other diasporic Global Southerners. Additionally, I draw from my own ancestral traditions, Maya and Nawat Indigenous epistemologies, as well as the popular education traditions of the Central American guerilla combatants and Central American teacher unions. My ethnic studies praxis is informed by ancestors and predecessors.

Though not cleanly captured in the Global South designation, Indigenous traditions like the American Indian Movement’s Survival Schools in Minnesota provide models for social movement education that aimed to instill self and community empowerment similarly to the Southeastern Indigenous education traditions of the Muskogee Creek, Cherokee, and Osage. The Black freedom struggle in the South has generated the models of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s Freedom Schools in Mississippi and Septima Clark’s Citizenship Schools in South Carolina. These mingled with the working-class white Appalachian model of the Highlander Folk School in Tennessee. Historically, the fugitive education strategies of enslaved Black people learning to read and write despite its illegality and the Black women teachers in segregated schools also provide powerful homegrown models for educational resistance.

Now, modern institutions are enriching the soil of educational resistance in the Global/U.S. South, providing liberatory learning spaces with youth and community. Radical Black-led organizations, including Project South, and Latine/x migrant justice organizations, such as Freedom University and the Georgia Latino Alliance for Human Rights (GLAHR), have expanded my sense of Global/U.S. South educational traditions.

Over the last decade, I have experimented with and continue refining a Global/U.S. South framework for ethnic studies alongside other educators and organizers. I have developed Latine/x studies classes at metro-Atlanta (and occasionally Northwest Arkansas) youth-serving nonprofit organizations, experimenting with this lens of Latine/x studies of the South. I have worked to embed this ethnic studies curriculum in middle schools and high schools through university-school partnerships in Georgia. Teaching Central America at Teaching for Change, where I work as a program specialist, have served as avenues to provide schools and teachers across the country with the tools to embed Central American studies in K-12 classrooms. Escuelitas, a collaboration between community-grown educators in metro-Atlanta, began in 2020 as a program to provide ethnic studies education to a multicultural, multilingual group of Latine/x and Indigenous parents and youth in the Buford Highway neighborhood of Atlanta. Through Escuelitas, we have developed a model for democratic, intergenerational, bilingual cultural and political education grounded in ethnic studies. Now, as far as we know, Migrant Roots Media is the first (though hopefully not the last) Southern-based institution to support the proliferation of critical consciousness, community, and social action for and about Central American Southerners.

The Structure and Pedagogy of Vos del Sur

The name of the program, “Vos del Sur” emerged as a play-on-words with “vos” – the second-person pronoun that many Central American countries use – and “voz,” which translates to “voice.” “Vos del Sur,” then, has the double-meaning of “You from the South” and “Voice of/from the South.” The subtitle, “A Central American Studies from the Global/U.S. South,” shifts the focus from the traditional Central American immigrant destinations like California to a neglected but crucial geography. Furthermore, the subtitle alludes to an analysis of the Global/U.S. South as a historically transnational, globalized region whose ideologies, policies, power brokers, and geopolitical relations fueled the conditions that Central Americans experience. It is also a region where Central Americans have settled for decades and now call home, even if home oftentimes hurts us through its racist, conservative, anti-immigrant landscapes.

Vos del Sur took place through Zoom between September 2024 to June 2025, longer than a traditional university course. The sessions, which were an hour and a half each, were scheduled on the last two Saturdays of every month. Participants were asked to contribute a sliding scale donation to the course, or to let us know if they needed a scholarship to be able to complete the course in the first place. Initially, we had between ten to twelve participants, all of them Central Americans who currently reside or grew up in the U.S. South, including in Georgia, North Carolina, and Tennessee. Over time, however, the group decreased in size to three to six committed participants per session. After all, it was a big ask to have participants meet on Saturdays to discuss assigned readings, documentaries, and other media for almost a year. Those who were able to stay gained much from the experience and contributed to this burgeoning field of Central American studies from the Global/U.S. South.

Based on the responses to a registration questionnaire, Ale and I selected only self-identified Central American Southerners to join the group, despite interest from non-Central Americans. We did this to create an intentional affinity space for our participants, particularly during the first year of the program. We are currently discussing the possibility of opening the class to a broader audience to create opportunities for inter-ethnic solidarity. The participants in the class ranged in age from their twenties to their forties. One of them was a college student in a nursing program; others were organizers for migrant justice, prison reform, and abolition. Some were master’s and doctoral students; others did not have college degrees. One participant was a technology specialist for a company; others were nonprofit program coordinators. Some participants were Honduran, one being Garífuna from the coastal islands of Honduras, others were Salvadoran, Guatemalan, Panamanian, and Costa Rican. Some participants were biracial, specifically Latine/x and white. The diversity in the group brought humility, multiple perspectives, and deeper learning.

The program culminated with participants creating their own cultural productions, be they traditional academic essays or more artistic media like poems and videos. The projects demonstrated their understanding of course content and established an archive for others to teach Central American studies from the Global/U.S. South through our voices. Although we formally concluded class sessions in April, the facilitators (Ale and I) hosted “office hours,” individual check-ins, and group work sessions to support participants in refining their projects between May and June. The Vos del Sur final project showcase took place on June 21, 2025. Participants presented their work and knowledge to an eager audience of Central American scholars, as well other friends and family.

Our class helped us make sense of the Central American experience and presence in the U.S. South not as an anomaly, but as a direct consequence of other U.S. South and Global South connections. In one of our first sessions, we read Aurora Levins Morales’ article, “The Historian as Curandera” from Medicine Stories: Essays for Radicals (2019), to understand the violence faced by colonized people and immigrants in an empire which manufactures historical forgetting and cultural disconnection. Levins Morales writes, “One of the first things a colonizing power, a new ruling class, or a repressive regime does is attack the sense of history of those they wish to dominate by attempting to take over and control their relationships to their own past.” Our lack of knowledge about who we are as Central Americans, especially as Central Americans in the U.S. Southeast, is a product of a colonial and imperial curriculum. Therefore, our class was medicinal in nature. Levins Morales further writes:

“The role of a socially committed historian is to use history, not so much to document the past as to restore to the dehistoricized a sense of identity and possibility. Such ‘medicinal’ histories seek to reestablish the connections between people and their histories, to reveal the mechanisms of power, the steps by which their current condition of oppression was achieved, through a series of decisions made by real people to dispossess them, but also to reveal the multiplicity, creativity, and persistence of their own resistance”

Drawing from antiracist, anti-imperialist, anti-colonial, pro-Black, pro-Indigenous, and transnational knowledges and approaches, a Central American studies from the Global/U.S. South aims to connect Central Americans in the South with histories that structure our place-making. It also sheds light on the racism and exploitation we experience in the Southeastern United States and the roots of our migrations from the Global South.

We integrated the canonical and emerging work of Central American studies scholars into the curriculum, including work by Leisy Abrego, Suyapa Portillo-Villeda, Kaysha Corinealdi, Steven Osuna, Jorge Cuéllar, Nicole Ramsey, and from the U.S. Central Americans (2017) anthology edited by Karina O. Alvarado, Alicia Ivonne Estrada, and Ester E. Hernández. We intentionally paired Central American studies texts with literature about the U.S. South broadly as well as with the more limited literature that exists about Central Americans in the South, such as Leon Fink’s The Maya of Morganton (2003). This gap in Southern Central American scholarship propelled us to become the storytellers, artists, scholars, and organizers who preserve and transmit our narratives.

Our program centered Indigenous peoples in Central America and the U.S. South through a land acknowledgement recited at the beginning of each session, as well as with deep engagement with texts about Indigenous peoples in what are now called the U.S. South and Central America. We also acknowledged the trafficking and exploitation of Black people in the U.S. South through a labor acknowledgement. Our syllabus integrated texts about the Black Central American experience and Central America’s ties to the Southeastern plantation complex.

The syllabus and class sessions aimed to be interdisciplinary by incorporating Central American art, poetry, and film across sessions. The curriculum spanned from Indigenous civilizations of the U.S. South and Central America all the way to contemporary Central American migrations to the U.S. South. We engaged with the Spanish colonial history of the Southeastern United States, particularly in Florida and Georgia. We studied the transnational nature of the plantation complex that enslaved Indigenous people first and then Afrodescendant people. However, we also looked at how the Garífuna people have a long legacy as free and migratory Afro-Indigenous peoples who pride themselves in resisting colonization and enslavement.

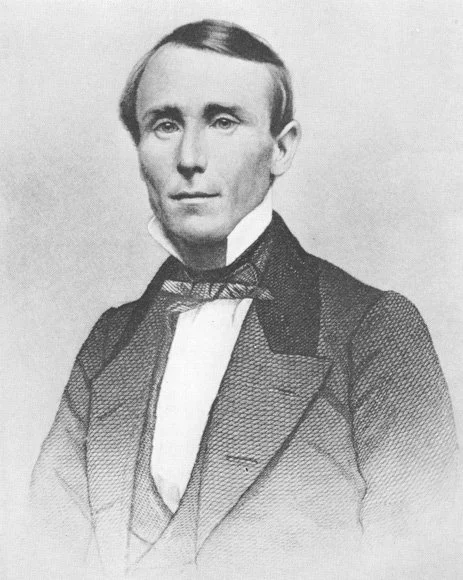

William Walker, the Tennessee filibuster who took over Nicaragua in 1856. He represents one of the canonical events in the history between Central America and the U.S. South.

In our unit about the colonial period in Central America, we discussed the infamous William Walker of Tennessee, who like other filibusters of the nineteenth century, invaded Latin America for power and profit in the region. Walker occupied Nicaragua in 1856 to expand the Southern slavery regime into Central America. He set a precedent for the domination of Isthmian land and labor to grow the infamous “Banana Republics” that circulated bananas between Louisiana and Honduras, among other countries in the Caribbean. Today, Garífuna and Honduran migrants are notably present in the South, namely Louisiana, in large part due to the Banana plantation regime that relied on their labor. Another thread in the U.S. South’s transnational efforts took place in the Panama Canal Zone where mostly Black people toiled to build the Canal in the early 1900s. During that era, the United States exported its Southern Jim Crow ideology and structure to Panama with long-lasting effects.

The School of the Americas (SOA) was founded in Panama in 1946 and was eventually relocated to South Georgia in 1984. This unit was key in our syllabus. After all, we cannot understand military dictatorships and revolutions in Central America without understanding the Global/U.S. South roots of the SOA. The transnational plantation complex and imperialist institutions like the SOA have laid the groundwork for modern immigrant policing and detention centers to wreak havoc on migrant communities in the Southeast. Our class unearthed connections between the Southern detention center network, the afterlives of slavery in the prison-industrial complex, the emergence of MS-13 in the United States, and Nayib Bukele’s dictatorship, which is influencing carceral logics in Central America and beyond.

In other sessions, we explored Palestine and Israel’s ties to Central America to expand our internationalist lens, inviting a Georgia-raised Honduran historian to demonstrate the connections between Israeli and Central American fascist regimes, prompting solidarity between the Central American and Palestinian people. A North Carolina-based Salvadoran anthropologist helped us situate the ongoing urbanization and land dispossession that shapes inequality and structural violence in El Salvador, including under Bukele’s regime. Yesenia Portillo from the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) described the escalation of Bukele’s carceral and anti-democratic regime and the social movements that have emerged in opposition. She made a call to action for diasporan Salvadorans and Central Americans to stand in solidarity with organizer Fidel Zavala and other advocates and human rights lawyers currently being persecuted in El Salvador.

A collage of the events during El Salvador’s civil war, among them the memorial to the victims of the massacre at El Mozote in Morazán and protests against U.S. intervention in El Salvador and Central America.

Just as oppression is a constant, however, the movements and revolutions of Central America and the work of migrant justice organizations were featured heavily in the curriculum. We introduced participants to revolutionary poets and artists like Roque Dalton through our ancestor acknowledgements and dedicated entire sessions to understanding the organizing of everyday workers and unions in Honduras. We studied and discussed the revolutionary, anti-fascist action of combatants in Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Guatemala. We examined the institution-building and migrant justice organizing of Central American refugees in the U.S. for migrant protections and to stop U.S. intervention during the civil wars. We also learned how labor organizing in the United States has benefited from the contributions of Central Americans, including Maya agricultural workers, in Immokalee, Florida, North Carolina, and Georgia.

The class was a dream come true, but we had to build it ourselves. We drew from the legacy of social movement education predecessors to find the wisdom and courage to build what has yet to be built. The goal now is to expand these models to further seed critical consciousness, self-love, community empowerment, and social action.

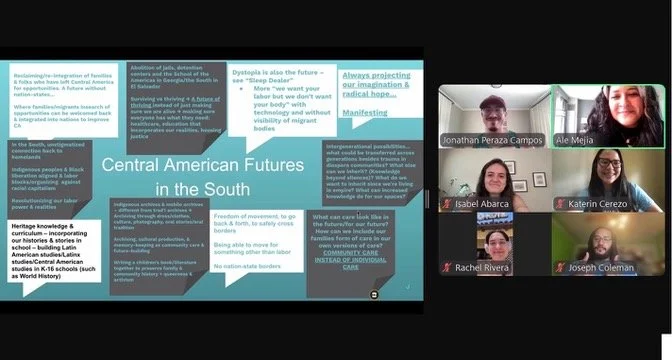

A screenshot from the last Vos del Sur class about Central American futures in the Global/U.S. South.

Lessons from Vos del Sur

In our almost full year of learning together, we uncovered several critical themes and lessons through Vos del Sur. We structured the program through a cohort model, meaning that we began with an initial group of participants that will be followed by other cohorts in future iterations. We hope to recruit participants from the first cohort to help facilitate future sessions of the program. By expanding the group of facilitators, we can share the responsibilities of coordinating the class and can train a cohort of people to teach Central American studies from the Global/U.S. South.

In terms of content, one of the themes that most resonated with participants was the emphasis on internationalist, transnational politics and multiracial solidarity coalitions. Throughout our units, we examined racial antagonisms between European criollo and mestizo elites and the Indigenous and Afro-Central American populations of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. However, in examining these racial dynamics in the history of Central America and the U.S. South, we solidified our commitment to antiracist and coalitional organizing. We also learned about powerful examples of multiracial labor organizing in Honduras and of white American and Central American organizing during the 1980s Sanctuary Movement. Thus, we concluded that internationalist, transnational, and antiracist organizing is key to a Global/U.S. South analysis. Hearing from guest speakers, especially Vos del Sur participant Nilson Barahona, was impactful in fortifying our commitment to multiracial organizing. Nilson, who spoke as a panelist alongside Amílcar Valencia from El Refugio, shared his story of ICE detention in Georgia. Furthermore, we watched a documentary he helped produce about his experience in detention, “The Facility.” Nilson was himself a cultural text, teacher, and student in our class. Joe Coleman, another one of our participants, found Nilson’s discussion very enlightening and said, “That’s what this class is all about,” making the connections between lived experience and course content. Participants were consistently encouraged to see themselves as experts of their own experiences. We are living cultural texts of the Central American South through our embodied knowledge.

Another set of themes that participants Joe and Bryan Mejía identified through the class is how learning about our histories and cultures helps us reconnect with our identity and homelands. Most of us had never experienced a Central American studies course in our lives. For many of the participants, this was the first and only ethnic studies class they had ever taken. Vos del Sur was even more responsive since we studied our politics and history as Central Americans in the Southeastern states where we were born and/or raised. For some participants, it helped them contextualize their family trauma. After all, some of the participants, including Isabel Abarca, had parents and other family members who survived and fled from the civil wars in either El Salvador or Guatemala. This class offered an opportunity to make critical connections between family history, war and genocide trauma, and U.S. migrations. Nilson also remarked during our sessions how the content about interventionism and neoliberalism helped him make sense of his migration story. Migration is often not voluntary, as we have been falsely taught, but a struggle to survive manufactured conditions often created or perpetuated by U.S. foreign policy and global capitalism. Through our learning, participants like Katerin Cerezo were able to intergenerationally transmit their knowledge of history and homeland to their families so that they too could learn about the histories and issues they had been deprived of in their schooling.

Participants like Nilson and Rachel Rivera commended the class for sharpening their political analysis, making them more effective migrant justice and abolitionist organizers in the South. We centered issues of migrant criminalization, legality, immigrant detention, and carcerality in Central America in the class. The class’s focus on Global/U.S. South relations helped us understand how migrant labor exploitation and detention are modern manifestations of the plantation complex, whose templates are embedded in Southern race and labor relations, especially in the rural South and in large agricultural production centers such as Immokalee, Florida.

Our final session in April emphasized Central American futurities. We explored the notion of Indigenous Futurism and Afrofuturism and how Central Americans, especially Indigenous Central Americans, have developed Mesofuturism in texts like Dream Rider by Salvadoran artist Daniel Parada. Although futurisms are a method of imagining alternative futures, we also discussed dystopia, such as that captured in Alex Rivera’s Sleep Dealer (2009). However, we ended the course with the creative and radical potential of imagining and organizing for the futures that we desire. We posed the questions: “What are images and key words that come to mind when you see the word ‘Central American Futures’? What do you want our Central American futures to look like? What about in the U.S. South specifically?” Together, we dreamed up this list:

Re-integrating immigrants who were forced to leave Central America into a welcoming Central America full of opportunities

Living a dignified life in the South without being stigmatized for our connections to homelands

Transnational solidarity between Indigenous and Black liberation struggles

Multiracial labor blocks that organize against racial capitalism both in the United States and in Central America

Access to the knowledge of our heritage through Latin American, Latine/x, and Central American studies curricula in K-12 schools and universities

Abolishing jails, detention centers, military bases, and the School of the Americas (later rebranded as the Western Hemispheric Institute for Security Cooperation, or WHINSEC)

Universal healthcare, free college, and housing justice so that we thrive, not merely survive

Archives that value our cultural apparel, photography, and oral traditions for the purpose of community care and future-building

Children’s books and literature to preserve family and community history

A future without nation-states

Freedom of movement, or the ability to travel safely across borders for reasons other than survival

Radical hope and community care instead of individual care

Intergenerational transferring of inheritances rooted in possibilities rather than trauma

Gaps and Opportunities for Vos del Sur

Throughout our class and in discussion with participants, we also identified significant gaps and opportunities. In terms of gaps, we noted that we only had one Afrodescendant student. In the future, we must be intentional in having more Afro-Central American, Afro-Indigenous, and Indigenous participants of Central American origin. We also did not have any Costa Rican (though a Costa Rican student briefly participated) or Belizean participants. Most of the participants were Honduran, a few Salvadorans, a few Guatemalans, and one Panamanian. Although the film “Eternos Indocumentados” directed by Dr. Jennifer Cárcamo explored trans Central American experiences, it was the only text to do so. More content that intentionally centers queer and trans Central American experiences and more participants of queer and trans experiences can enrich our class. Similarly, a focus on disability justice issues in the Central American diaspora is an area of inclusion and analysis to incorporate. Another area of emphasis to consider for our curriculum and discussions is how rural and urban contexts both in the U.S. South and in Central America contribute to differential political activity, ideologies, and experiences, as Rachel pointed out. Urban and rural spaces offer both possibilities and limitations for Central American communities that should be explored.

Though we started the class with about ten to twelve participants, halfway through the program, our numbers reduced to a smaller but very committed group of six to seven student participants. We should explore the factors that contributed to the turnover rate of participants and based on that data, brainstorm methods for retention. Moving forward, opportunities that we intend to pursue are the training of participants from past cohorts to facilitate future classes. The goal is to proliferate Central American studies classes, especially that those that emphasize a framework of the Global/U.S. South.

During our concluding session titled “Central American Futurities,” we engaged in an exercise of creativity and critical imagination. Together, we composed a group poem titled, “Intergenerational Worldmaking.” This poem captures the legacy of our Vos del Sur program.

Intergenerational Worldmaking

by the 2024-2025 Cohort of Vos del Sur –

There is so much to destroy

But there is so much to create

We are mountains & volcanoes

From architectural and mathematical feats in our veins

From the earth and elements around us

We honor the oral testimonios of our ancestors to redefine our future

From banana fields to southern dirt, we toil

We are strong now, have always been and will continue to be

We weave a world that sees us playing under the hot Southern sun

Tending to and transforming our collective wounds to create new worlds

Learning our history from our own people

1 Our conception of the U.S. South includes the states of Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Jonathan Peraza Campos is an Atlanta-based Central American educator, organizer, graduate student, and co-founder of Vos del Sur. He builds ethnic studies infrastructure and supports Southern ethnic studies organizing through his middle school teaching and work with Escuelitas on Buford Highway. At the national level, Jonathan’s work as program specialist for Teaching Central America at Teaching for Change supports schools and teachers across the country with developing Central American studies in K-12 education. As the co-founder of the Vos del Sur program at Migrant Roots Media, he and Alejandra Mejía curate a space for Central Americans in the U.S. South to learn their history, forge an identity, and build community. He hopes to use all his experience in research and teaching toward collective liberation.