It Feels Like a Miracle to Be Alive

Brief Background

To engage deeply and meaningfully with this project and these stories, an awareness and acknowledgment of the historical and sociopolitical context that they are told from and shaped by is helpful. Since the late nineteenth century, the United States has cast its imperial net across Central America via political, economic, and military agendas [1]. In El Salvador, where this project’s narrative begins, anticommunist efforts led to the 1932 massacre, known as La Matanza, and continued with the civil war that spanned from the late 70s until the signing of the Peace Accords in 1992. The United States provided millions of dollars and military support and training [2] to the Salvadoran government during the civil war resulting in mass displacement and immigration. Salvadoran refugees fled the war and traveled north to the United States where they were met with more violence, through the systemic denial of asylum. This, of course, would require the United States to implicate themselves if they were to grant asylum to refugees fleeing a war that they were complicit in [3]. Central American scholars Karina O. Alvarado, Alicia Ivonne Estrada, and Ester E. Hernández make clear that “the influx of migration that occurred post-1980s as well as current diasporas and recent migration trends are intrinsically connected to the economic, political, and military strategies the United States planned and then deployed onto Central America as a region and to each Central American nation.” [4]

This project includes two main narratives. Part I is based on a story pulled from an oral history interview I conducted with my father, Miguel, about an event from his childhood in El Salvador. Part II offers a personal reflection of my childhood and what it was like as a mixed, U.S. Central American growing up in the U.S. South. An audio recording, with various speakers reading the text, is also available. The audio for Part I includes the voices of my father, my little brother, and myself while Part II is voiced by my father, my older brother, and myself. This is an intergenerational project and story.

Prologue

It feels like a miracle to be alive.

Not because of a close encounter with death—no—this isn’t a feeling that can be traced back to a moment in my own life but rather to a collection of events in my parents’ lives, and their parents’ lives, and their parents, and so on.

To be alive and be of those who have come before me, feels like a miracle.

For my father to have survived to see his 13th birthday is a miracle, for my great paternal grandparents to have made it through La Matanza is a miracle.

And for my really, really great maternal grandparents to have made it to what we now call the United States after traveling across the Atlantic Ocean in the 1600s is a miracle, and a tragedy.

It feels like a miracle to be alive, through the movement, displacement, and violence that my ancestors have survived and, in certain circumstances, that they have also enacted.

The miracles (and tragedies) are riddled with complexity and contradictions.

A 2nd generation Salvadoran immigrant; a 12th generation (give or take 1-3 generations) English immigrant.

It feels like a miracle to be alive, yet to be here, at the heart of empire, in the United States of America, carries its own collection of challenges, burdens, and responsibilities.

Part I: It’s My 13th Birthday Today

Authors and narrators: Miguel (b. 1967), Isabel (b. 1994), and Mateo Abarca (b. 2016)

April 6, 1980: San Salvador, El Salvador

It’s my birthday today and I still can’t believe I’m alive.

I’m hot, bruised, and in so much pain. This crowded cell is so uncomfortable. I’ve only been in prison for a couple of days and honestly, I’m just glad to be alive.

I didn’t think I would survive to see my 13th birthday.

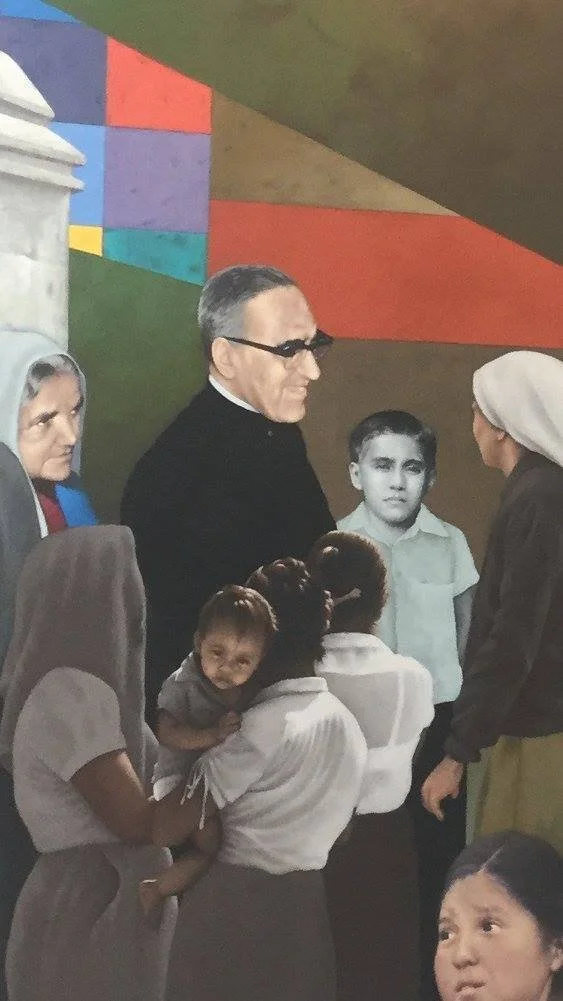

A little over a week ago, I made it to San Salvador all the way from Morazán to try to find my mother and go to the funeral of Monseñor Romero [5]. I was able to find my mom and told her I was going to the cathedral, to the funeral. The next morning, on Sunday, I walked there, alone.

There were thousands of people, shoulder to shoulder, but everything was peaceful.

Everyone gathered to mourn and cry, some people said their goodbyes from the street outside of the cathedral and others were able to walk in and pay their respects.

It must have been around 2 or 3pm when everything changed [6].

Everyone started screaming, bullets began raining down.

The massacre had just begun.

There was already so much panic, as innocent people dropped to the ground, limp, the streets were soon covered with blood.

Military soldiers were lined up on some of the highest buildings and shot anyone and everyone they could.

They had this all planned out.

As I looked around, no one on the street had guns or any way to protect themselves or those around them.

I couldn’t believe this was happening.

I was so scared and sad.

I couldn’t move without stepping on and over dead people.

As I tried to push myself through the crowd, I saw a pregnant woman on the steps of the cathedral. She got stuck under the railing and couldn’t get up or move, people were running over and around her. She was screaming for help.

I tried to make my way towards her, but I couldn’t move either, I was stuck.

My feet and body were caught in the crowd and only able to move once others around me moved and had to step over and around the dead people and masses in the streets.

I couldn’t hear her screaming anymore. I looked up and she looked at me; I’ll never forget her or that moment, her gaze, a look between two people fighting to survive.

She died soon after that.

I couldn’t get to her fast enough and my heart broke. There were so many dead people, children, women, and men whose bodies covered the streets and the steps of the cathedral.

I still can’t believe I’m alive.

The sun started going down, bodies were being loaded into trucks, and I somehow found a place to hide, inside a McDonalds. I stayed there until it was dark, and the shooting stopped. I wanted to leave but some of the other people wouldn’t let anyone open the door.

Everyone was afraid and hoping to survive. Desperate to survive.

But I think once the streets were cleared, they started searching all the buildings and started taking people back out onto the streets and into trucks, or worse.

When they got to McDonalds, they opened the doors and started firing, killing many of the people I sat next to and talked to. The rest of us were arrested.

I walked out with my hands on my head, and they tied me up before forcing me into the back of a truck.

It was so dark, and I couldn’t move, I couldn’t scream, I couldn’t cry. I was so terrified and felt like I was there forever. I don’t remember if I fell asleep or how time moved. But I kept thinking that I would never see my mom again, that this was the end.

They took us to la policía nacional and I was brought into a room all by myself.

At this point, I didn’t know if it was night or day. Time was hard to tell.

They beat me up and asked me questions, I think they wanted answers that I didn’t have. And the less I said, the worse it got. They got more and more mad, and the violence and pain got worse. But I couldn’t say anything because I didn’t know anything.

They tortured me. They pulled my teeth out, including my front tooth, and put electric wires on my arms.

I hear one of the men say that they’re going to kill me.

They kept torturing me. I couldn’t survive this; I was going to die.

This was the end.

After what felt like a very long time, I heard American accents outside of the door and then a knock. The Red Cross was looking for political prisoners and my screams caught their attention.

They found me and took me out of that room, the room I would have died in.

I was taken to an infirmary. They tended to the worst of my wounds and stopped the bleeding from my mouth and other parts of my body.

I only stayed there for a couple of days before they transferred me here, to Mariona.

I’m 13 today.

I’m a prisoner, where I’ll probably be for the next few years but I’m alive, for now. I can’t believe I’m here, breathing.

I didn’t do anything different from the other people last week, from the thousands who died.

It feels like a miracle to be alive.

Part II: In My Kentucky Home

Author: Isabel Abarca; Narrators: Miguel, Pablo (b. 1991), and Isabel Abarca.

in my kentucky home

201 cornell place

martha maud birthed her second child,

a daughter of a daughter of a daughter [7]

in the home that she shared with her husband

“1994 Bartlett/Griswold highlights:

Martha, son Pablo, and a cloud of witnesses welcomed home-born Isabel”

30 years later, sitting on my grandmother’s couch, a block from where I was born

flipping through the family archive of newsletters

a subtle but noteworthy refusal…

overlooking…

protecting…

but miguel ángel was there, too, right? yes

bearing witness to his daughter’s birth, the beginning of her life

the daughter of a father of a daughter

when memory includes him, years, decades later

his presence is described as a performance, arriving just in time

and quick to act out his fatherly duties

step 1. cut the umbilical cord

step 2. hold newborn baby (your daughter)

step 3. pose for a family photo (tip: smile, be sure to look like a happy family)

two weeks old, or was it one?

when miguel ángel left his kentucky home,

my, our, kentucky home

an absence arriving upon his departure

a cavity that appeared before I knew what life had and could have held

left to make sense of home and family through what was and wasn’t there

left to make sense of our kentucky home

the spaces that extended beyond cornell and oxford place

it was in school where we first felt the weight of difference,

a difference that could only be explained by what (or who) we didn’t see or know

“you ***** Mexicans,” a phrase that too quickly slithered out from the mouths of our classmates

friends who would too easily joke about border crossings

and who would pick apart and judge our appearances

not enough

too much

my brother would stand up to these injustices

he tallied up fist fights in school and confrontations with neighborhood kids

I, on the other hand, took a far less noble route

a coward; terrified to upset or disrupt

pouring my energy into wishful thinking

wishing to exchange my brown hair and eyes

for something, anything, lighter, blonder, bluer

to exchange and change what I looked like

and who I was

“My Old Kentucky Home:

History, Harmony, Hospitality!

Kentucky’s Premier Destination

Welcome Home

Tour the Plantation” [8]

my Kentucky home

often did not feel hospitable

harmony only available when history can be ignored

and silenced, a premier destination for who?

I was nine years old when fragments began to surface

in fourth grade I met my father

these visits would last for a few days and then we’d wait

and wait

it would be 6 or 12 months until we would see him again

in my kentucky home(s)

we moved from one place to the next

but we would always come back to oxford place, our sanctuary

a home filled with love and joy and family

a home with English as its official (and only) language

one that was filled with U.S. american foods, toys, and customs

full

my childhood was full

my mouth, lips, and teeth knew mac and cheese, rice milk, meatloaf, and jello

my eyes and sight familiarized with white, blonde, and blue

my ears, mouth, and tongue knew only one language

leaving me unable to speak to my abuelita luisa

my childhood was full

yet there was an absence, a gap that happened to contain worlds

worlds that my brother and I are deeply connected to

a lineage that has given us life

ancestors that were persistent to survive but that were difficult to trace

in and from our kentucky home

betrayal is the feeling that has and continued to come up

as a child I felt betrayed by what wasn’t there

what I didn’t learn, what I didn’t see, and what I didn’t eat

betrayed

by what I didn’t have in my kentucky home

haunted by not knowing

for years I wondered

why – how – could my dad leave his 3-year-old son and his week-old daughter?

how could my mom not see the multitudes that we, her children, carry?

from the second we entered this world

our bodies aching to transgress the temporal and spatial landscapes of our bluegrass state

worlds that we embody…

salvadoreña

united statesian

U.S. central american

salvadoran child of diaspora

born and raised

in my kentucky home

life was fragmented, but, and full

full of family—cousins, uncles, and aunts who lived close by

and the frequent family activities of soccer playing, carpooling, and vacationing

I adore my cousins

and they have effectively expanded the categorical notion of ‘immediate family’

full of love and stability unconditionally offered by grandma

and mom, she loved us deeply and dearly

neither cooked very well or with much flavor but we stayed fed, full

over time, martha and miguel overflow their exclusive parental molds

as I feel them stretch and spread into humans, friends

with stories and histories to hear, witness, and understand

where they’ve been and who they are

knowing that they did the best they could

loving unconditionally and fully

my childhood marked by fragmentation, fullness, plurality

but, and

it feels like a miracle to be alive,

to be the daughter of martha maud and miguel ángel

to be the granddaughter of katharine griswold, maria luisa, miguel ángel, and douglas bartlett

to hold and carry the worlds of those who have come before me

to know and honor the survival and joys of my kin and ancestors

and to map out the responsibilities of my inheritance

as the daughter of migration and sanctuary movements

living in the heart of empire

working towards and hoping to disrupt and upset

to hope for a better world for my children and my children’s children.

Outro – pieces of my father’s and I conversation after he read Part II <3

[1] Alvarado, Karina Oliva, Alicia Ivonne Estrada, Ester E. Hernández. 2017. U.S. Central Americans: Reconstructing Memories, Struggles, and Communities of Resistance. University of Arizona Press.

[2] Gill, Lesley. 2004. The School of the Americas: Military Training and Political Violence in the Americas. Duke University Press.

[3] Alvarado, Estrada, and Hernández. 2017; García, Cristina. 2006. Seeking Refugee: Central American Migration to Mexico, the United States and Canada. University of California Press.

[4] Alvarado, Estrada, Hernández 2017, 19

[5] Now saint, San Romero.

[6] Background noises in the audio clip are pulled from various sources: https://www.youtube.com/@APArchive/search?query=el%20salvador%201980, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oF1OTx7GbW4, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k4MscBN9UxQ, and others from Instagram from Los Angeles, California June 2025 when the National Guard and LAPD are sent to repress and attack community members protesting the recent immigration raids.

[7] Duan, Carlina. 2021. Alien Miss. University of Wisconsin Press. Page 82.

[8] This language comes from home page of the website (https://www.visitmyoldkyhome.com) for the former plantation called “Old Kentucky Home” which is claimed to be one of America’s most iconic 19th-century homes.

Isabel Luz Bartlett Abarca was born in Kentucky to a Salvadoran father and a U.S. American mother. She is the proud sister to older brother, Pablo, and younger brother, Mateo. She currently lives in Durham, North Carolina and is pursuing a doctoral degree in anthropology at UNC Chapel Hill. Her dissertation research is focused on intergenerational relationships and the role of memory and storytelling among diasporic Salvadoran families.