Recovering Maya Roots

Cover image: Me planting tomatoes during my fieldwork in Cotzal, June 2014.

It took me a long time to feel comfortable and without hesitation to self-identify as a K’iche’-Maya. I was born and raised in Los Angeles and come from a working-class background. My parents migrated to the United States from Guatemala during the early 1980s. While I will not delve into the specific details of their story here, I attribute their migration to structural inequalities and violence that force people to migrate, sometimes even flee, and find a place to grow elsewhere.

Guatemala suffered a 36-year U.S.-supported Civil War (1960-1996), in which 200,000 people died, 83% of these victims were indigenous, and 1.5 million were displaced. The Guatemalan military, which collaborated closely with the U.S. military and government, was responsible for 93% percent of these deaths. The remnants of the war in Guatemala continue to be characterized by structural racism and violence, impunity, corruption, and poverty which has continued to force people to flee. During the 1970s and 1980s, thousands of Guatemalans were displaced to cities such as Los Angeles, Houston, New York, and Miami.

Cotzal, Guatemala, 2019

Growing up, I did not know or care about my roots, and was not fully conscious of my ancestral and indigenous backgrounds. There was not one exact moment that led me to recover my Maya identity; but rather, there were seeds of memories planted in my childhood that would later germinate into questions that I would come to harvest in my adulthood. I remember asking myself why I did not have a “Latino surname” such as López, González or Gutiérrez, and asked, “what the hell is a Batz?” I remember some people telling me that it sounded like a European surname. As it turned out, Batz (spelled B’atz’ in the Romanized K’iche’ alphabet) is an ancestral day name within the Maya calendar. It means “howling monkey.”

Another seed of memory was going to Guatemala for the first time in 1992 as a six-year-old, 500 years after the Spanish invasion, and seeing my abuelita, Clara Coyoy Ixcot (1921-present), in her Maya dress from Xela. As a child, I did not think much of it, and just thought that’s what abuelitas wore in Guatemala. These personal memories, questions, and realizations would later become the basis for reclaiming and affirming who I am. My abuelita’s teachings and stories are characterized by perseverance, survival, and dignity. They dignify my spirit, heart, and mind.

Cotzal, Guatemala, 2019

In the process of recovering my indigenous roots, I encountered people who engaged in repressive authenticity and strategic essentialism to deny my K’iche’ and Maya identity. I often heard comments in the United States and Guatemala, such as, “you were born in the U.S., how can you be Maya?” “you don’t speak K’iche’, you’re not Maya,” “you are a fake K’iche,’” among others. One of the most head-scratching criticisms that I received was, “you don’t even speak good Spanish, how are you indigenous or Guatemalan?” The notion of speaking a colonial language as a prerequisite for being indigenous is rooted within colonial logics of repressive authenticity. It is important to note that Guatemala is a settler state, based on patriarchal white supremacy and the erasure of indigenous peoples. When discussing Independence from Spain, the question we should ask is: independence for who? There is a reason Spanish is the dominant language in Guatemala and Maya languages are viewed as inferior. Historically, indigenous peoples in Guatemala have been subjected to forced labor, suffered territorial dispossession, marginalization, and structural violence; mainly because the system and the nation-state was not built for us.

Oftentimes in academia, indigenous peoples are represented and objectified through the words, vision, and colonial gaze of non-indigenous peoples. However, more and more indigenous and Maya people are beginning to write our stories outside and inside the walls of the Ivory Tower, which has historically been a pillar of colonialism and an extractivist industry of knowledge. Challenging the colonial logics of the Western academy is necessary to conduct research in an ethical and committed manner with the communities and peoples we work with, as well as to avoid over-romanticizing and over-theorizing concepts and events without providing solutions to problems on a practical, real-life level for people on the ground.

Cotzal, Guatemala, 2019

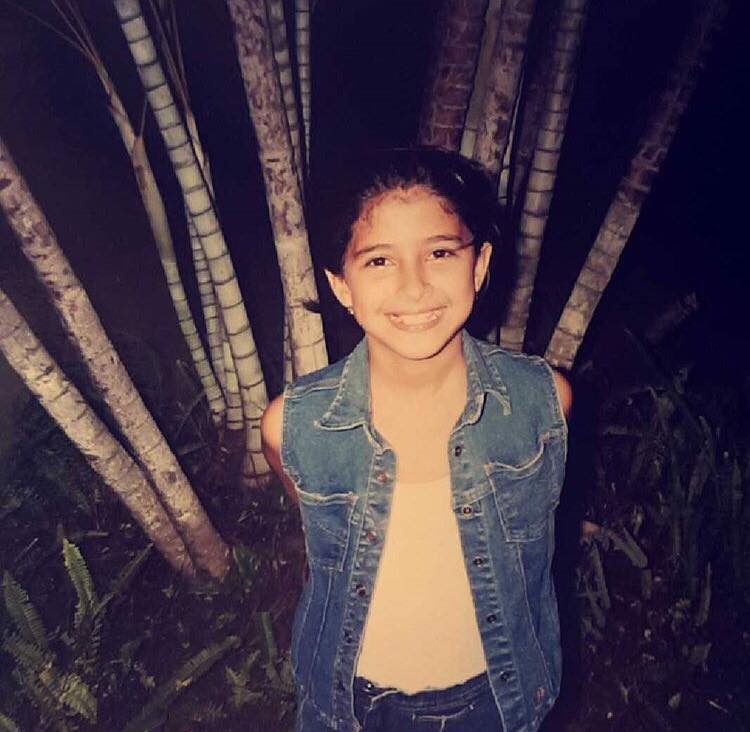

While some of us were born or raised outside of ancestral territories, where our ancestors’ spirits live in the mountains, the rivers, the fields, and the forest, their struggles and legacy flow through our blood, our being, and our memories. One of my proudest moments as a father, was having the privilege to take my daughter, Ixq’anil, to the land of our ancestors and seeing her begin to collect her own seeds of memories. That we are physically here in this world, that we remember, and that we are writing our own stories as Maya and indigenous peoples, is a profound demonstration of our ancestors’ resiliency to survive, as well as thrive against oppressive structures.

Dr. Gio B’atz’ (Giovanni Batz) is a Visiting Assistant Professor at New Mexico State University in Las Cruces, and received his PhD in Social Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin. He was a 2018-2019 Anne Ray Fellow at the School for Advanced Research in Santa Fe, New Mexico where he began working on his book project, entitled “The Fourth Invasion: Decolonizing Histories, Megaprojects and Ixil Resistance in Guatemala”. The book is based on nine years of research conducted in Cotzal, where the arrival of megaprojects is referred to as the “new” or “fourth” invasion. B’atz’ has also worked with Guatemalan-Maya youth in Los Angeles, as well as conducting research on migration of K’iche’-Maya from Almolonga, Quetzaltenango. He served as a tutor and facilitator at the Ixil University between 2013 and 2015.