Healing Across Borders

—> Content Warning: This article contains graphic descriptions of violence and murder.

My hands tremble. My nose aches the way it does just before tears form, or like when you're underwater, flip too fast, and water rushes into all the wrong places. A spider has been weaving webs of excitement and guilt down my spine throughout the flight. Now, the threads have reached my fingertips. That’s why they tremble.

The pilot’s voice crackles overhead, “Hemos aterrizado en la Ciudad de Guatemala.” Can this really be my life?

How can someone feel so full and so empty all at once? This should be my mom. This should be my sister.

How ungrateful. I shut that book and shove it into a shelf in my mind, one I’ll open later.

But I am finally here. Mi Guate.

It almost didn’t happen. For years we spoke of this return like it was a fairytale. To see my grandmother again. To stand in the place where both beauty and violence live in the soil.

Now, my two worlds collide: the story of the five-year-old who left and the twenty-three-year-old woman who returns.

My grandmother standing among her plants in the sacred space where she conducts rituals and daily spiritual practices. The garden represents her connection to Maya cosmology, herbal medicine, and the continuity of Indigenous healing traditions within our family.

My journey from San Juan Zacatepéquez to Atlanta is not a story of abandonment or assimilation, but one of transformation and return. Through my work as a nurse, I carry forward a legacy of healing passed down from my grandmother, a Maya priestess who cares for her community through spiritual and ancestral medicine. I carry both stories, here and there, to build a liberated future.

Migration, Displacement, and a New Life

To me, it felt like an adventure. Like one of those camping trips on TV. We floated on car tires through a river. It felt as exciting and scary as hide and seek. Quiet, secret, thrilling. Even my mom seemed like she was playing, she was very concentrated and kept asking us to keep quiet. But this was no game.

I was five. My mom was nineteen. My aunt was only seven. My sisters were four and one. And there were men with us, coyotes, though I didn’t know that word then. I remember my grandmother driving us to the drop-off in Mexico. I slept most of the ride. When we arrived, my grandmother cried. I told her, “No llores, mami,” thinking we’d be back by dinner. But she cried and prayed, her tears soaking into her shirt. She gave us necklaces with colorful stones, something beautiful to carry across the unknown. After that, the days blurred. I remember my baby sister wanted to cry from exhaustion. My mom tried to breastfeed her to keep her quiet. The men told us we had to be dead silent for our own safety. At this point, I could feel it wasn’t a game anymore. Eventually, we started our new life in Texas, then Atlanta.

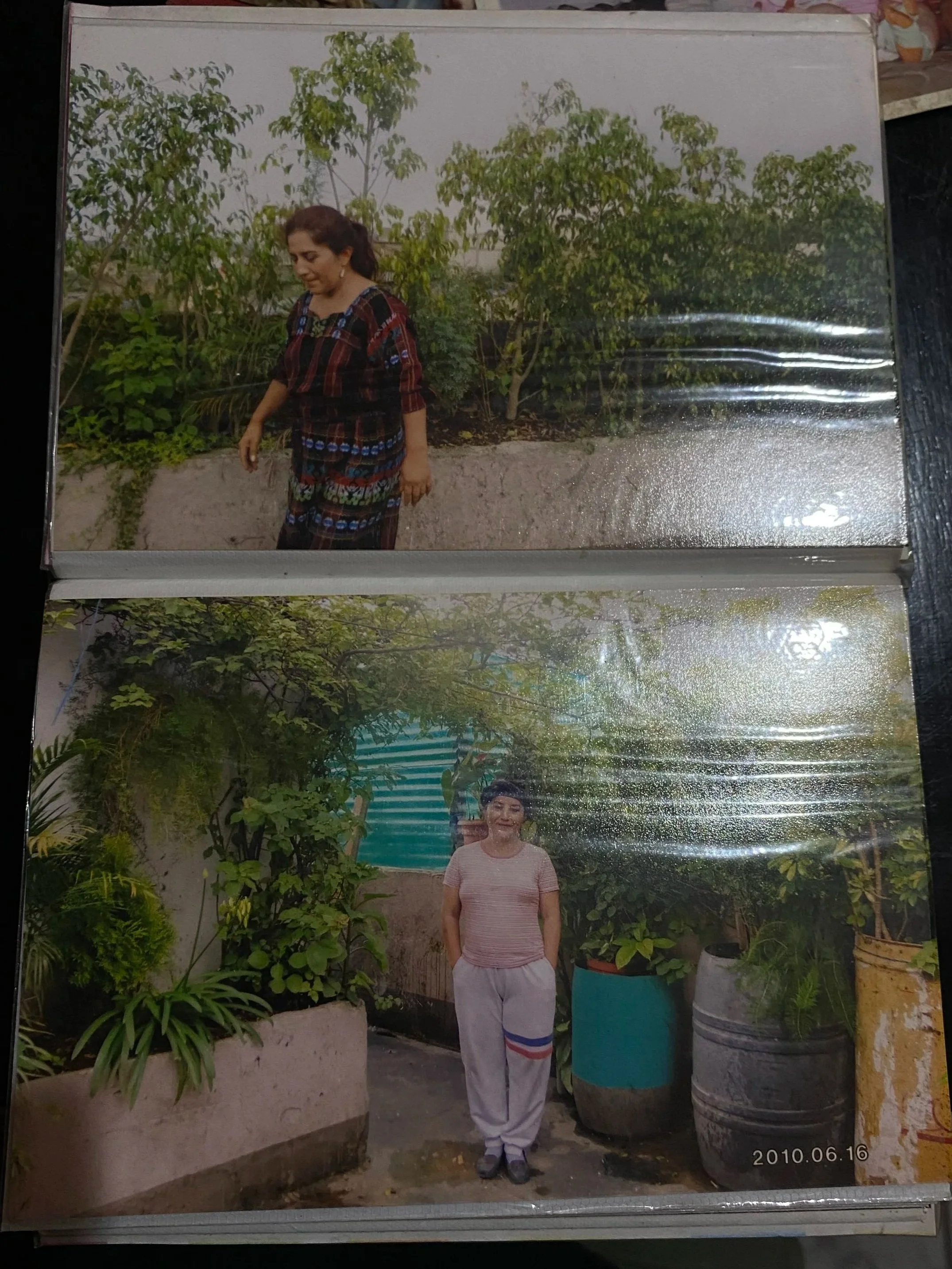

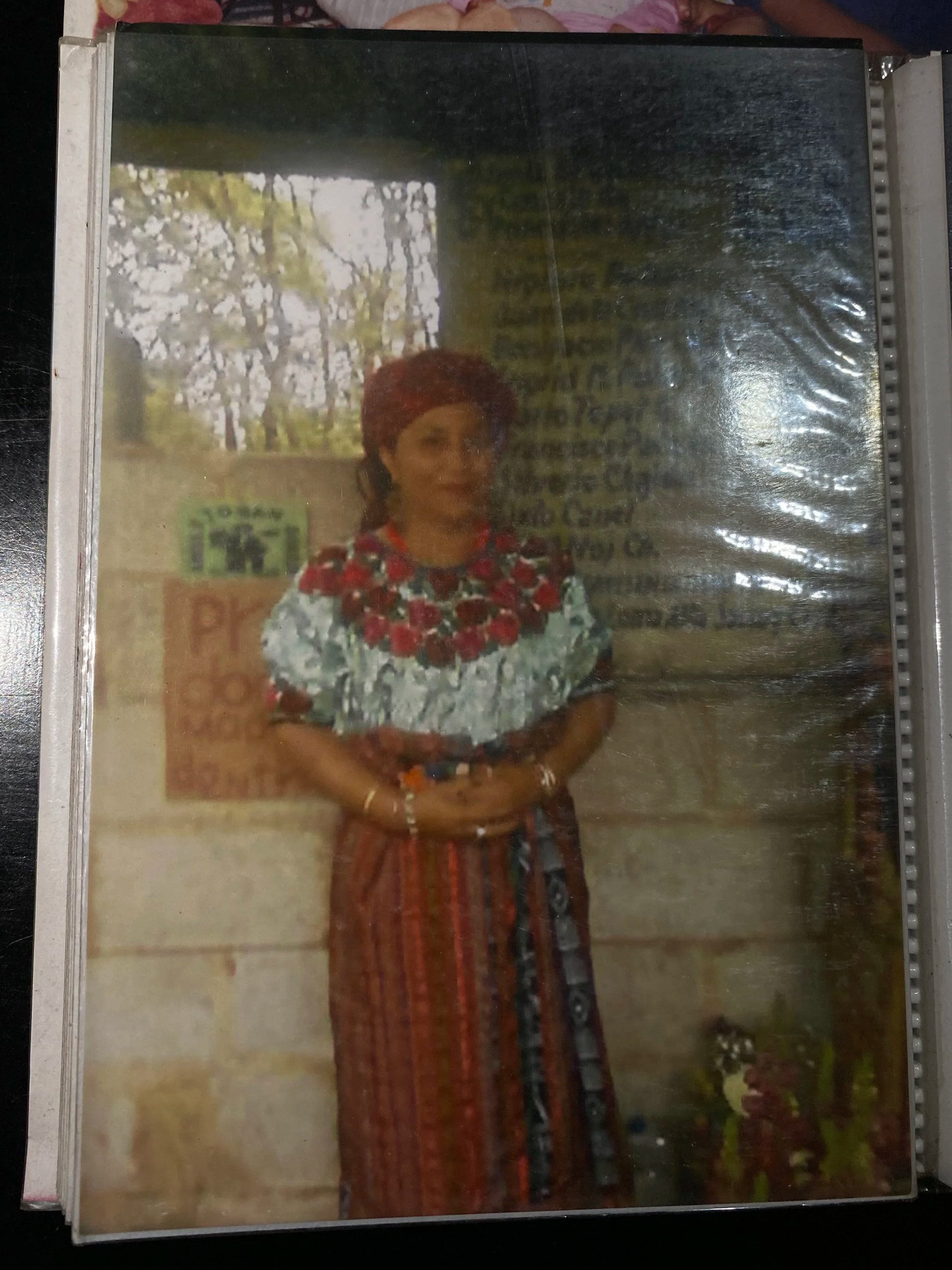

Family photograph in Guatemala in the early 2000s. This image accompanies a timeline of historical events discussed in the essay, illustrating how personal and collective histories intersect across generations.

I used to ask my mom, “Why didn’t we stay in Guatemala?”

She would say, “Aquí sí hay trabajo. Aquí sí puedo cuidarlas.” Back home, jobs were scarce. Our community had little electricity or running water. Many children started working at the young age of five. My mom wanted us to have a childhood filled with safety and freedom from worry, a stark contrast to the chaos and hardship she endured in her own upbringing. To have the chance to dream. Poverty was not the only thing she was running from; she was also escaping the pervasive threat of femicide, which is integrated into society.

Guatemala has a dark history of femicide, which has thrived because of the patriarchal society that the Spanish left in their wake when they introduced Christianity and the nuclear family. Colonial structures and ideologies dismantled Indigenous practices that focused on community and shared gender roles and replaced them with a hierarchy where women are subordinate and men are all-powerful. Christianity further reinforced this social order by commending obedience, modesty, and silence as proper virtues for women; in that same breath, they legitimized male dominance within households and in society. As time passed, these imposed norms infiltrated and became part of Guatemala’s political, legal, and cultural institutions. This created a perfect breeding ground to perpetuate systematic inequalities that allow gender-based violence to thrive. The persistence of femicide is a virus in Guatemala that was inflicted by Spain’s imperial rule and has only grown and festered over time.

My mother, thirty-nine now, still carries the memory of finding her sister hanging from a rope, her legs and feet touching the bed in a way that made it clear that she had not done that herself. Actually, it’s impossible that she could have done it herself. She held her sister’s body as it shifted from the warmth she felt a few hours ago to cold and stiff as rigor mortis set in. My mom knew no one would be held accountable for ripping her best friend away from life. That grief, that fear, became her reminder and warning that if she stayed, she could be next. If not her, then any of her three baby girls. That was a risk she was not willing to take.

My aunt’s murder was not an isolated tragedy; it’s a part of a larger pattern of violence against women in Guatemala. In many ways, femicides are also rooted in the legacies of war, where sexual violence is used as a weapon.

According to a 2017 paper published by The Advocates for Human Rights, in the first ten months of 2015, Guatemala’s Public Ministry received 29,128 reports of domestic violence and more than 11,000 reports of sexual or physical assault, alongside 501 reported violent deaths of women. Behind each number is a story just like my aunt’s. Each number is not only a loss of life but also of safety, possibility, and trust in justice. I can only imagine that these numbers have exacerbated since.

On that same note, all of this is unfortunately multiplied for Indigenous Maya women. A recent study found that about three-quarters of women who experienced violence also suffered depression, anxiety, or suicidal thoughts; however, almost none received care or attention. Many Indigenous Maya women described their experiences as being filled with fear, shame, and exhaustion, which was intensified by barriers to courts, language discrimination, and state neglect. The trauma they carry is not confined to memory, but has become embodied, manifesting as headaches, insomnia, fatigue, and persistent sadness that endures long after the violence has ended. Despite these conditions, they continue to resist every day: through the labor of motherhood, the endurance of silence and survival, and the preservation of spirituality, drawing strength from the resources of which the state has tried to deprive them.

Displacement Is Not Random

After Indigenous communities were displaced, their lands became sites for mining and corporate development. How convenient. The 1996 “Peace” Accords in Guatemala weren’t about healing. They were about opening the door to international capitalism. But I will get to that in a second.

My family’s migration was not a coincidence or personal failure. Like many of our families, it was a consequence of war, corruption, and empire. One that doesn’t begin in Guatemala, but in offices in Washington and in campgrounds like Fort Benning in Georgia.

My Guate is beautiful. It is a land of volcanoes, mountains, rainforests, and coastlines. It’s the blue of Lake Atitlán and the cobblestone streets of Antigua. It’s a paradise rich not only in natural goods but in culture, ancestral knowledge, and spirit. And yet, millions of us have been forced to leave. That contradiction is at the heart of Guatemala’s geopolitical relationship with the United States.

We didn’t migrate because we couldn’t see the beauty and richness of our Guatemala, alive with the voices and spirits of our ancestors. We migrated as the consequence of empire. The 1954 CIA-backed coup that overthrew democratically elected President Jacobo Árbenz opened the door to decades of U.S.-supported military dictatorships, genocidal campaigns against Indigenous peoples, and neoliberal economic policies that concentrated land, water, and wealth into the hands of elites. As the film Eternos Indocumentados by Jennifer A. Cárcamo makes clear, “People don’t leave everything they love unless they have to.” My family was one of many who had no choice. To stay meant risking poverty, persecution, or death.

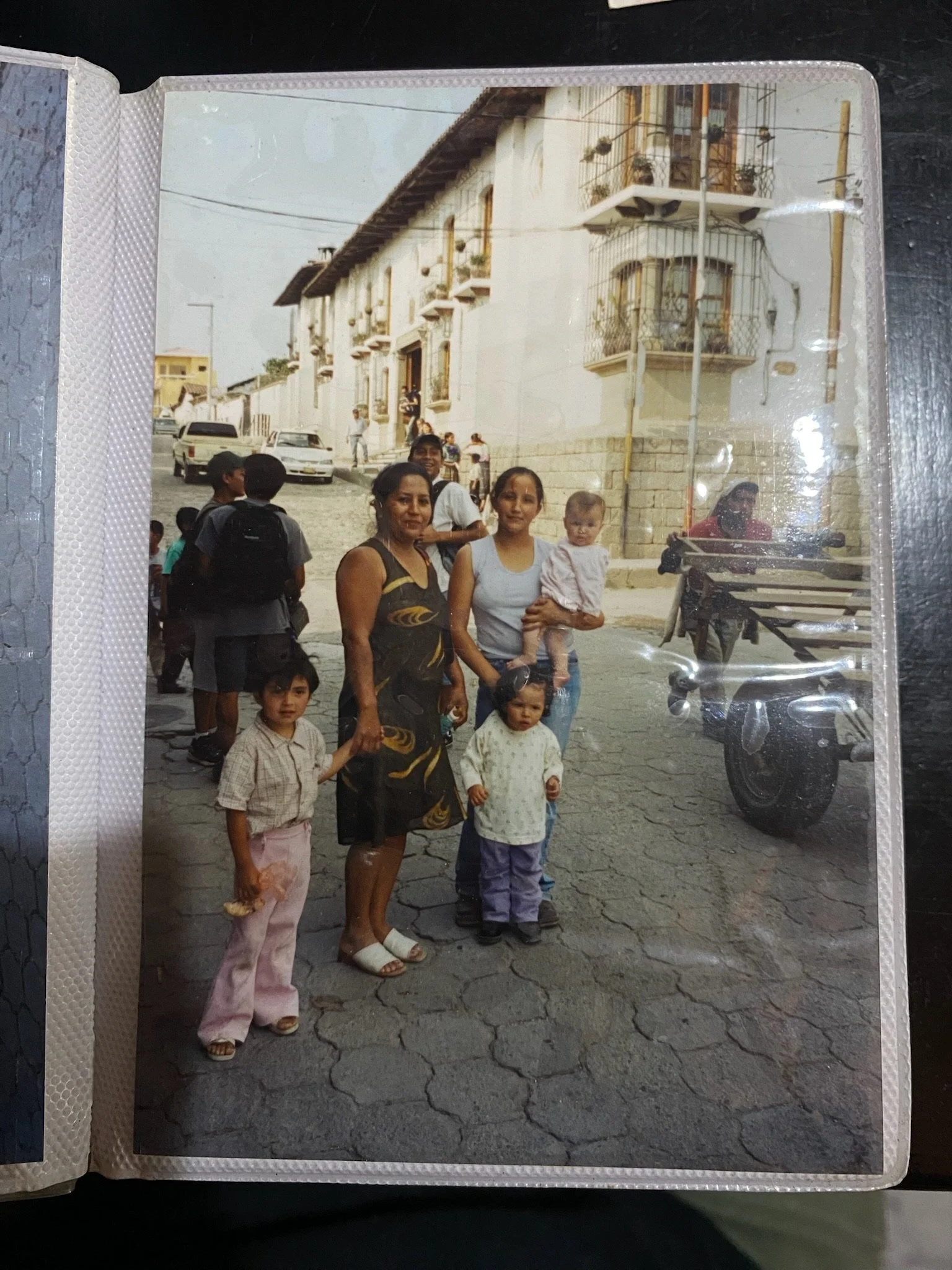

Timeline connecting key historical events in Guatemala.

What makes this even more personal is that I now live in Georgia, in the U.S. South, the very region where so much of this violence continues to be orchestrated. The School of the Americas (SOA), now the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation (WHINSEC), located at Fort Benning, GA, trained thousands of Central American military officers in torture, counterinsurgency, and repression. Anthropologist Lesley Gill writes that the SOA, “Helped to militarize Central American societies and legitimize violence against civilians in the name of fighting communism.” These weren’t abstract policies, they recruited men from our very towns and trained them to turn on their neighbors. As Dévora González and Azadeh Shahshahani explain, SOA/WHINSEC continues to fuel militarization and anti-migrant violence across the Americas today.

Guatemala’s relationship with the United States is not one of mutual diplomacy, it’s a story of extraction and control.

In 1952, President Árbenz passed an agrarian reform law that aimed to redistribute unused land to poor and Indigenous farmers. However, much of that land was held by the U.S.-owned United Fruit Company, which immediately lobbied the U.S. government to intervene. Under the false pretense that Árbenz was a communist, the CIA launched Operation PBSUCCESS, a covert mission authorized by President Dwight D. Eisenhower. In 1954, Árbenz was ousted in a military coup backed by the United States, and the democratically elected government was replaced by a dictatorship. The United States trained and funded hundreds of Guatemalan military personnel, including Carlos Castillo Armas, who was installed as president after an election in which only he was allowed to run. He jailed political opponents, reversed land reform, and opened the country to U.S. corporate interests.

What followed was more than four decades of state-sanctioned terror. Castillo Armas and the military regimes that came after him initiated and enabled the genocide of the Maya people during a civil war that lasted until 1996. But the so-called “peace” treaty that ended it was not written for the people; it was written to make the country safe for foreign investment. The regions where atrocities occurred were cleared, then leased out to mining companies, agribusiness, and megaprojects. As Aurora Levins Morales explains, imperial powers seek to erase memory and rewrite land histories, making exploitation seem, “Natural, inevitable, and permanent.” In Guatemala, genocide was not just a crime of war, it was an economic strategy.

Soldiers isolated rural populations in so-called “model villages” controlled by the army, cut off from food and medical care, as a way to root out alleged guerrilla sympathizers. Since then, thousands of bodies have been exhumed from these camps, which have shown that many of our peoples’ cause of death were “malnutrition and treatable illnesses.”

These were not benevolent development projects, but rather brutal acts of state repression disguised as governance. The 1996 Peace Accords ended open warfare, but not corporate land seizures. Many sites of genocide were swiftly transformed into mining zones, hydroelectric dams, and export agriculture, cementing the dispossession of Indigenous lands.

Our lands were stolen for bananas, our rivers dammed for foreign profit, and our labor funneled into U.S. industries while our communities were left with nothing. Levins Morales calls this “imperial history,” a story imposed on us to justify exploitation. But she also reminds us, “People who are being mistreated are always trying to figure out ways to end, avoid, or lessen that mistreatment… they nevertheless represent a form of resistance.” Migration, healing, organizing – these are our forms of resistance.

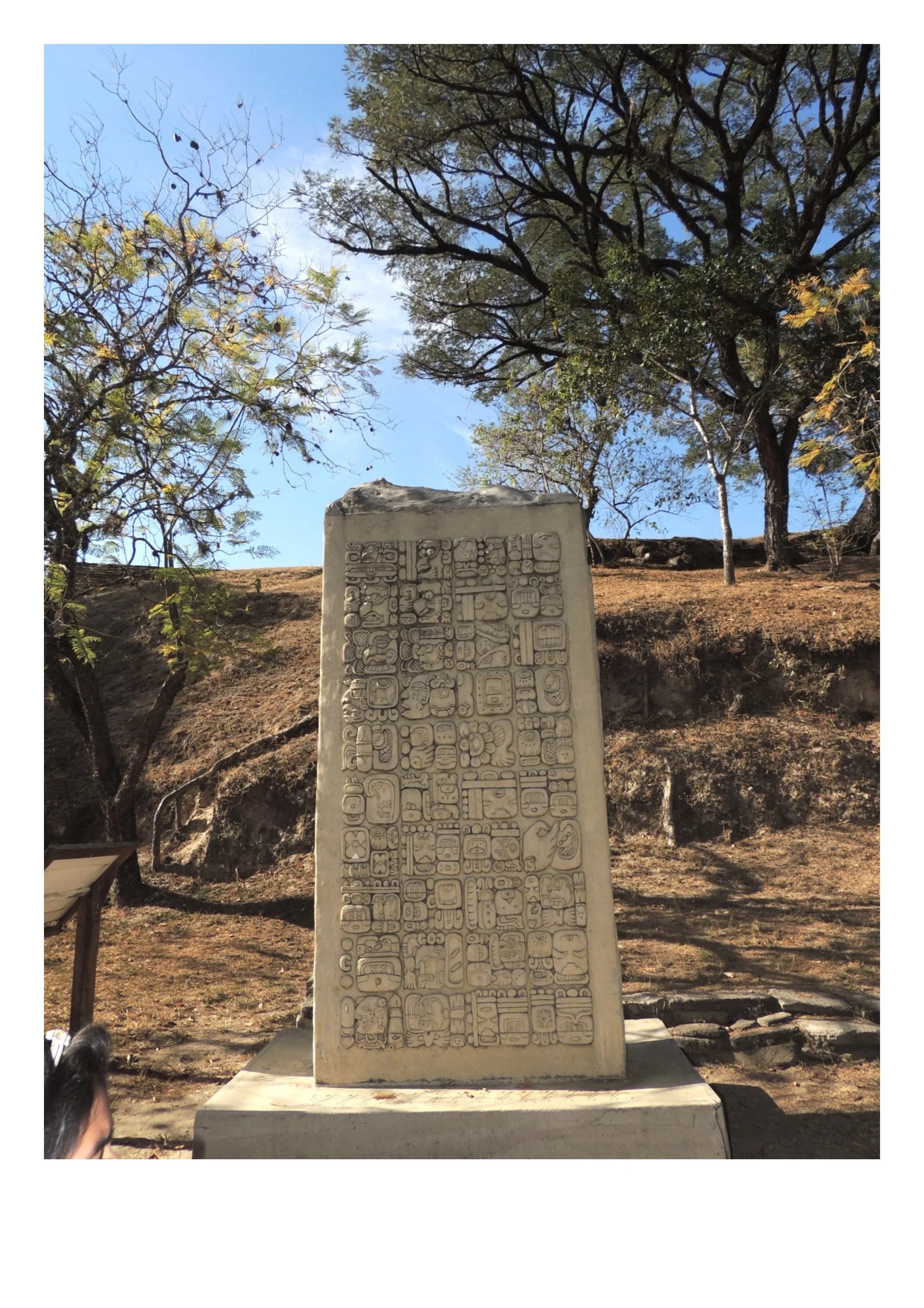

A carved stela at Utz Ipetik, a sacred site where Maya priestesses, including my grandmother, perform ceremonial worship. The inscriptions symbolize ancestral knowledge and spiritual resilience that have survived centuries of colonial erasure.

Violence Is Cyclical

And now, I live between two homes, here in Georgia, and there in Guatemala. This is my home, and that is my home. It’s borderless. I don’t have to be in one place to belong or to resist. I am resistance. I am resilience. I feel my people, and they feel me. We feed off each other’s energy, off our ancestors, off the land. And because of that, we are never truly separated. We are one people, bound by memory, spirit, and the unwavering will to survive, and to thrive.

But still, I know there is so much more of Guatemala I haven’t experienced. There are mountains I haven’t climbed, dialects I haven’t heard, memories I haven’t yet remembered. These words I write don’t do it justice, maybe because I’ve studied science and I am trained to speak what is presented as fact, not feeling. But the truth is my Guate, and all the homelands of the oppressed, are overflowing with energy, the kind that can’t be measured, only felt. The kind that lives in the bones of our ancestors, in the hands of curanderas, in the wind that speaks through banana fields.

Violence is cyclical, and while Guatemala suffered displacement and patriarchal impositions under Spanish imperialism, the Muscogee were displaced from this land by Anglo-American settler colonial forces; both reflect the same broader imperial system that thrived on dispossession, enslavement, and the domination of Indigenous peoples. Violence is cyclical.

My grandmother wearing traditional attire, preparing for a ritual ceremony. Her dress and stance embody cultural pride and the living continuity of Indigenous spiritual identity despite historical and ongoing marginalization.

I studied nursing at Emory University in Georgia as an undocumented student who often didn’t know where I belonged, or why I was even allowed in the room. I carried guilt and shame that were never mine to bear. But through Vos del Sur, through hearing history from people who look like me and who refuse to frame migration as a “dream” to ease their own conscience, I feel more connected, more grounded, more free. I want to hear more voices from our people. Migration will not stop. And we can plant stories for the next generation of immigrants, so they will know who they are, who we have been, and what we have survived as proof of our resilience, our pride, and our permanence. We are here, and we are not going anywhere.

When I went back to Guatemala with Advanced Parole, I felt as Maya Chinchilla in The Cha Cha Files, finally reaching the “imaginary homeland.” However during my time there, I was not just a visitor. I was a returning healer. I felt connected to my grandmother, someone who heals through herbs and energy. I didn’t just visit her; I became part of her. The healing she began with plants, I now continue with stethoscopes and IV bags. We are not separated by medicine. We are linked by purpose. We both bring life.

This is how I resist. This is how I remember. This is how I return again and again.

Katerin Cerezo is a Guatemalan-Salvadoran immigrant from San Juan Sacatepéquez, Guatemala who has lived in metro-Atlanta for over twelve years. She is a proud first-generation college graduate from the Emory School of Nursing and is deeply passionate about education and healthcare equity both in Georgia and in her home countries. Vos del Sur gave her insight into Central America and its connections to the U.S. South, and she is excited to share her work and continue building community through knowledge.